<<back to sevensixfive forward to 765>>

Six days on the Eimskip container ship Dettifoss, July 2005

19 July, Tuesday

I'm nervous that I won't make it to the airport in time to catch my flight, I misjudged the timezone shift and the overnight ferry from Helsinki to Stockholm has gotten in an hour later than I had guessed. This is going to be an exhausting day until I get on that boat. So I take a bus from the ferry terminal to Centralterminalen, and there I buy a ticket for the 1 hour + trip to Skvasta airport. While waiting for the bus I realize that if I have to go to the bathroom I should go now ... but you have to pay to use the restroom and it only takes 5 Kroner coins. I have no Swedish Kroner, only Euros left over from Finland, so I wait in line to use the ATM, and then wait in line to buy a candy bar at a kiosk because the machine has given me nothing but 100s. The man two people in front of me is attempting to pay for two sodas with a credit card, but he apparently does not know how to use his credit card. He tries four times. He calls his wife over. He tries again. I have to go to the bathroom. I may miss my bus. I am wearing a very large backpack, it's extremely heavy. He finally gives up and his wife pays in cash. I buy my candy bar and get my change and then wait in line to use the toilet. It has no paper towels. Why am I paying to use a bathroom that has no paper towels?

Then on the bus for an hour ... more Swedish countryside, I'm not paying attention, though, reading Dante's Divine Comedy instead - it's good to read older classics when traveling, classics or material that relates to the place you're staying or going to. We arrive at an airport that's smaller than some houses I've been in, and everyone on the bus gets in line to check into the same flight I'm on. I ask the German couple behind me how far the Lubeck airport is from central Hamburg (Centrum) and they say: "Oh not far, just about one hour shuttle bus ride, it's easy." Thanks Ryanair, cheap but very inefficient. The security guard at the metal detector stops me for a moment to look in my backpack: "You've got a lot of electronic gear in here, sir." That's right. The flight takes an hour and 10 minutes, so that means with the trip to Hamburg I'll be on buses for twice as long as I'll be in the air.

At Hamburg Central Station the first cab driver I approach is completely confused by my desire to go to the port: "Try him, he speaks english," indicating an African guy driving the next cab down. I try my schpiel on him: "The Freeport? Busshansa terminal? Number 80, 81?" "Yeah, I know the port but I don't understand this address." "We'll figure it out, let's try it." I say, and we're off. 25 Euros later we're rolling through stacks of containers five stories tall. "Down there and to the right." the guard says, when I ask about the Dettifoss. And there it is, the name on the bow, already half full and still being loaded. "This is it." We're getting the bags out and the cab driver is laughing at me: "Are you going to ride in a container?" "I hope not, I'm going to Iceland." He just laughs, sure kid.

I have no idea what to do or where to go, I'm standing there shooting pictures of everything in sight, a total rube with a huge backpack on among all these containers, dangerous machines, and guys with hardhats and neon jackets. What the hell? I get on the ship. "Authorized Personnel Only." That's me. Authorized. I wave like an idiot at the first person I see. "Hi. I'm Fred, I'm a passenger." And by passenger I mean moron. "Yes." he agrees. "I'll show you to the ship's steward." So I meet Jonas, the steward, and we climb seven flights to my cabin. That's fine with me, the higher the better. He unlocks the door to an impossibly palatial room right below the bridge with table, chair, couch, fridge, television, VCR, stereo, closet, huge bed, and bathroom. "This is your cabin." "Wow, that's great!" I'm still in slack-jawed yokel mode. "Thanks!"

So I unpack, explore the ship, and meet the German couple who are my co-passengers. They're having their caravan packed in a container and brought along with them to drive around Iceland. "That sounds like a fantastic trip." I say. They're full as full of superlatives as I am: "Yes. We love to take fantastic trips!" Dinner is good and hearty, beef and potatoes and cabbage and peas. Solid. "Hello" I hear, and turn around. "Hi! I'm Fred, I'm one of your passengers." "Yes. I'm Matthias, the Captain." And so he is, his name is sewn into his shirt above the pocket in case I hadn't believed it. Captain Matthias Matthiasson is an Icelandic man about the same age as my Grandfather, with a buzz cut, glasses on a string, and a crushing handshake. "I don't want to disturb your dinner, but if you have moment, please stop by my cabin and give me your passport for the register." After dinner I come up to see him. "So you are an architecture student in Finland, then you must have been visiting the work of Alvar Aalto!" he predicts, correctly, "and you are going to Iceland for ... what?" I tell him I'm interested in cities, and seeing how people live, and landscape, and he seems to buy that. "Yes, yes, yes. You know my favorite architect is of course Frank Gehry! I went to see, in this city called ..." "Bilbao?" "Yes. Bilbao! On the same quay that I used to bring Eimskip ships into, he has built a Guggenheim! My wife and I went to see it, and we spent two days! I also love art, my favorite artist is Richard Serra!" I tell him Eisenman's story about Helmut Kohl and the Jewish Monument in Berlin. "Yes." "Of course I also love american tiazz!" "I'm sorry, what?" "Tiazz! American cultural phenomena, tiazz!" "I'm sorry ..." "You might say 'ji-yazz' " "Oh! Jazz!" "Yes. I collect everything I can!" "Well, I don't know much about jazz, but I like 'Kind of Blue' and 'Sketches of Spain' " "Yes." He gets up and walks over to a cabinet, pulling out a 6 disc box set "This is 'Kind of Blue' " "The sessions?" "Yes." "Wow." "I have to stay interested in something here! Because I am not interested in ships and containers!" he said.

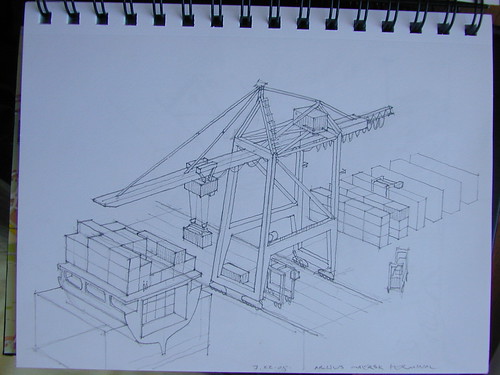

I explore the ship and the area of the quay around it, amazed that no one stops me and asks me what right I have to be there. I watch the loading process wishing I had a video camera. Flatbed trucks with containers on their backs pull underneath the large behemoth cranes. The cranes can slide along the quay on pairs of tracks, spaced about thirty meters apart. A grabber drops down from the underslung gantry cabin and latches onto the container. The operator lifts it up, and both the grabber and the operator's cabin slide out along a long rail until they're over the ship. The grabber is lowered and the container is released. It takes maybe 45 seconds to load one container this way, and by the time it's unloaded there's already another flatbed waiting, the flatbeds are loaded by vehicles that look like giant dune buggys, with big grabbers slung up and over their backs like scorpion stingers. The tricky bit must be figuring out in advance where to put the containers and coordinating the loading sequence so that it's efficient and correct. The long rails of the behemoth cranes are folded up when they're not in use, and this profile of the four-legged crane with the rail pointed at the sky like a deer's neck is the typical one that I had associated with industrial harbors in Baltimore. Back on board I settle into my cabin with Dante and doze off, we're due to leave Hamburg at 4am.

20 July, Wednesday

As promised, the ship is rumbling at 4. I get up to watch out the cabin window. After a few minutes of preliminary murmur, we're under way and I'm back in bed. Yesterday my phone and I had an argument, it told me that if I couldn't remember the otherwise useless PIN code that came with my SIM card then it wouldn't tell me what time it was. At this point all I need the thing for is as a clock, the minutes on the card are dead, and I don't plan on calling anyone from the North Sea, anyway. But the geniuses who invented this SIM card system decided that the phone, which is also a calculator, stopwatch and alarm clock, would become a paperweight if the user ever forgot the arbitrary four digit number that came with the last recharge he or she got, in whatever random Scandinavian country he or she was in, when the thing ran out of minutes last. I've been traveling for too long. I had cursed it and pulled the battery out. So that meant that when I got up I had no idea what time it was. I looked outside and saw a sleek catamaran with "PILOT" on the side and assumed we were being led into the harbor at Goteborg and it was mid-day. I was wrong, we were still on our way out of the river from Hamburg and it wasn't yet 9 am. I had almost missed breakfast but Jonas still had some stuff out and I ate it alone.

Afterwards I went for a walk around the ship again and went upstairs to read some more. I dozed off and and when I woke, the ship was rolling and we were out in the North Sea. Outside was a thousand shades of grey: the water churns with waves at 7-10 feet and the sky is shot with dark patches everywhere loosing angled, blurry rain on the horizon. Breaks in the clouds let the sun spotlight through and turn bits of the sea to shiny silver, the only color anywhere is the turquoise being thrown up in our wake. After staring at this from the couch for several minutes, I was questioning the stability of my breakfast. I decided it would be wise to lay down and read after typing only made it worse. Reading was good, the rolling ship was fun as long as I couldn't see out the window, and the churning in my stomach turned out nothing worse than some harmless burps. I was asleep again before long ...

And so the day went. Eating: with breakfast at 8, lunch at 12, coffee and cake at 15:30, and dinner at 18:00, it's not hard to stay well fed. Reading: Divine Comedy, Lonely Planet's Scandinavia book, and the Aalto Guide. Sleeping: lying down is the most comfortable position for reading, and who can resist being rocked to sleep by the North Sea and a full belly. I took a total of about three naps, one after every meal, none more than an hour long.

The only break was when Goodman, the Second Officer, invited me to come visit the bridge: "That sign that says 'No Passengers- Restricted Access', don't pay attention to that." There I found only the Captain, standing steadily despite the horizon which was pitching from the top of the wraparound windows to the bottom, with jazz on the sound system. "Is this satellite radio?" I asked, reaching for a railing to grab onto. "No. It is a Danish Jazz station! Denmark is just over the horizon to the West!" He indicated a slightly darker patch of grey off the starboard side. "So it just takes one person to pilot the ship?" The cabin I was occupying was marked "pilot" over the door. "Yes. It is all done with computers!" He showed me the GPS map, and the radar. Small alerts and alarms go off whenever the ship is drawn off course by current or wind, or when the radar senses an immanent collision. "This weather is terrible!" he said, turning on the wipers for the frontmost windows. "Is there usually only one person up here?" I had been struck by how undesigned the ship was, the interior could be a boring hotel, on a roller coaster. There are very few windows or opportunities to make sense of the ship as a whole, but up here, on the bridge there is literally a commanding, totalizing view of all of the containers, the length of the ship, the sea in every direction. "Yes. We only need one person usually, when coming into port, sometimes two." The Captain was standing easily with his hands crossed thoughtfully behind his back. I tried uselessly to keep up with the endless rocking, hanging on to a counter and trying to look casual. "Do you ever got bored of the view?" The Captain snorted and turned to Goodman, who was looking through some charts in the back, and said something to him in Icelandic like: "Boy, this guy's a complete idiot!" Goodman laughed and agreed. "Yes. After fifty years of this, yes I get bored of the view!" the Captain told me. "How long have you been a captain?" "In 1973, I sailed an Eimskip ship to Cambridge, Maryland, as captain." I asked him about the containers: "How do you know that something you need to unload in Goteborg isn't buried under something you need to bring all the way to Torshavn?" "Ah! The operations officer works all that out, with the help of the computer!" He gestures towards an empty chair. "It is all decided in advance. Almost never do we have to shuffle! And not only that, the weight must be calculated as well, evenly distributed so that the ship does not roll over or break." "So the computer optimizes for two variables: the order in which you load and unload, and the evenness of the container's weight." "Yes."

I was a little worried about the persistent uncertainty in my stomach. It seemed to make anything other than reading into a potential disaster. In my cabin I went back to Dante, I had been hoping to catch up on this journal, and maybe do some drawing and painting as well on the trip, we'll see ... I was also worried about how easily I would be able to sleep that night with all the naps I had taken during the day, but the rolling sea and lower lattitudes took care of that, it's good to be away from the midnight sun again and have a nice long, dark, night.

The crew of the Dettifoss:

Matthias Matthiasson, the Captain, loves art, Richard Serra, and Jazz: "You know, Tiazz!"

Bragi, the First Officer, spends a lot of time in front of a computer on A Deck, he's the one to go see if you need shore leave.

Goodman, the 2nd Officer, wears a flannel shirt tucked into sweatpants.

Jonas, the Steward, cut his hand today trying to catch a knife.

"Chief Engineer", the Chief Engineer

And the passengers:

Wilifred (sp?) and ???? a couple from Hamburg "We love to take fantastic trips!".

and Myself.

21 July, Thursday

A little late for breakfast again but Jonas still had everything out. We had slid into Goteborg harborat about 6 that morning, and the view outside was still dimmed by clouds and spitting rain. I could see a large field of containers, bigger than at Hamburg. Two cranes had already manouvered alongside us and were unloading containers, which were being picked up by tall four-legged vehicles painted safety orange. These have the same dimensions in plan as the containers, and after the boxes are set on the ground by the behemoth cranes, these vehicles roll over the containers on eight wheels and pick them up with a grabber that runs in the center of their long dimension. Just like the big cranes, these are designed to move things in the x, y, and z axes, with the added ability to roll around and turn. These vehicles I think of as harvesters because here they take the place of the scorpions and flatbeds at Hamburg. The harvesters can roll into the wide container fields and pick up fresh containers from above, they're probably about 12 or 15 meters tall and can grab containers even when they're stacked three high.

The whole process just begs to be completely automated. There's already a map of the position, destination, source and weight of every container aboard the ship, and I'm sure that's coordinated with a map that the terminal has of every container in their possession.If that were linked to a unique RFID signature for each one then the harvesters could just travel along a buried wire to find the container they were looking for in the x, y, and z dimension, verify it's identity and precise location with RFID, grab it with magnets at the corners and put it down under the behemoth. The behemoth triangulates the RFID signal to get a fix on it, picks it up, and puts it just where it needs to go on the ship. To ensure safety you probably have a person riding the crane, but you don't need drivers for the harvesters, just give every human on the ground out there a kill switch to use if it looks like a harvester's about to run them over, or better than that, give them RFID too and the harvesters can just steer around them. The stevedores, or as we call them in the states, longshoremen, are becoming the latest group of tradespeople to be put out of their jobs by robots. The ships already practically steer themselves, that's why I'm staying in the pilot's cabin, "there is no pilot". The course of the ship is plotted in advance as a series of vectors with turns at key points. The ship's computer lets the officer on duty know when it's time to make a turn, and corrects itself with GPS (or maybe Galileo as a reference during the straight runs. The origin of word "cybernetic" is "kybernetes" - steersman in Greek. So the arrangement of cargo and the logistics of operations are already optimized by software, the next step will be to link that software directly to the hardware of cranes and harvesters and turn them into robots. They willhave a set of large goals and priorities, and the kind of basic decision making processes that the ship uses to stay on course autonomously: avoidance and correction.

The implications of this tendency towards automation are already apparent on the ground. I was allowed to run around taking photographs among the containers at Hamburg because the major movement of containers is done by guys driving regular trucks. The drivers of the harvesters at Goteborg are four stories in the air, and are more concerned with the location of containers than the location of tourists, and so are more likely to hit anyone who isn't trained to stay out of their way. Going ashore in Goteborg is a process that begins with a visit to the office of Bragi, the First Officer, he gives me my passport from the safe and calls the terminal office for a transport to come and pick me up. A few minutes later, a minivan with an orange light on top arrives and we drive to the gate, where there is a city bus stop. All the cars that circulate in the terminal have these warning lights on them, and they all apparently move clockwise around the quays and to the gate, staying in their own clearly marked lane. As in Amsterdam, the modes of transport are clearly segregated from one another by their relative levels of deadliness. The behemoths stay on their wide tracks and beep conspicuously whenever they're moving, cars and peds stay in their zones marked by stripes on the ground, and the harvesters have the run of the of the place, it's their territory, and it's left to anyone who is less dangerous to stay alert and alive.

I took the bus to the tram to the city, amazed at how far out from "Centrum" we were. In the past four days I've driven over 800 kilometers in 10 hours from Rovaniemi to Helsinki, took a cab to the Silja Line Terminal, ridden the Baltic Ferry for over 15 hours, took a bus to the city center, then another hour long bus ride to the airport, then an hour and 10 minute flight before taking another hour long bus trip to the center of Hamburg, followed by a half hour cab ride to the Busshansa Terminal and the ship. At that point I had come all the way from the Arctic Circle to central Germany in two days. And then after 24 hours in the North Sea here I am back in Sweden. The itinerary for the Eimskip line would take me back to Sweden and Denmark, and this almost made me reconsider signing on for the trip, but now it's obvious that arriving at the container port of a city is not the same as coming by train right to Centralstation with the pedestrian shopping zone and hotels ten steps away. These are areas that are not designed for human habitation, these environments are laid out to the specifications of the large vehicles and machines that inhabit them: the ships, the cranes, the harvesters, the containers, and the trucks. The ships keep getting larger, that can be seen in the central stair of the Dettifoss where there is a gallery of photographs showing the four other Eimskip ships that have borne that name. A few people have written about how this tendency of centralization, along with containerization and automation of the process pushes the industrial harbors further and further away from Centrum, where there is deep water to bring in big ships, and wide open land to let the vehicles run around in. A lot of the people who got on the bus with me at the various terminals didn't bother transferring to the tram that would take them to the center of town, they're going to their homes in the suburbs. This cuts the city center out of the loop for the remaining humans who work in these places as they move between different locations around the edge.

But Centrum's still doing fine. Goteborg, like Stockholm and Malmo, seems not to lack for places to shop and people to shop there. The pedestrian streets are being covered, as in Milan, and turned into shiny indoor malls. Who knows what all these people are doing at the mall at 11 am on a Thursday? Are they all on shore leave from various container ships, maybe? I needed to get cookies, some movies to watch on the ship, and a new SIM card for my treacherous cell phone, and had no trouble finding all of those things, including the tourist office and an internet cafe, without getting lost.

I made it back to the ship in plenty of time despite the transfers, thanks to the rationality and ease of use that are the hallmarks of Scandinavia's public transportation system. There and back again with one ticket that cost about $2.50. I spent some time drawing the stack of containers and the orange harvesters. Although it's sunny out by now, black clouds still swoop in and drop spots of rain for a few minutes at a time. At coffee I talk about architecture with the Captain. He tells me that the new Opera House in Copenhagen, a ridiculous looking spaceship with with a baseball cap on top, on axis with the Royal Palace, was endowed (and half designed) by the chairman of the shipping company Maersk. And that Maersk, as it's prerogativeas the largest shipping company in the world, has caused Eimskip's original schedule to be rearranged. "Why do we go to Goteborg before Arhus?" I ask. "Yes. That is a good question! We used to take the canal that leads from the Elbe River in Germany to the Baltic, and stop at Arhus on Thursday and Goteborg on Friday. But Maersk has said that it needs to use the entire harborin Goteborg every Friday, so that means we come on Thursday instead now and add 12 hours to our schedule by going all the way around Denmark!" He tells me that I will soon see one of Maersk's large ships, the Axel Maersk, over 350 meters long and 40 meters wide, carrying 7,200 containers to Dettifoss's 1,453, pulling in this evening. "I have a video you might be interested in!" he tells me. "About the ports?" I ask "No. About Frank Gehry! and Bilbao! Probably you have already seen it!"

Later I'm drawing some more and when it starts to rain again, I move into my cabin to try to color the drawing of the harvester I had made. The Captain knocks on my door, he has the Frank Gehry movie. "I have brought you this movie! Probably you have already seen it!" I tell him that it's not likely, and thank him. "And also this!" the Phaidon book of 20th century art. "It has some of my favorite artists in it! And these!" two jazz CDs "For you to copy! On your computer if you wish!" I thank him and show him the drawing that I'm working on, he looks at it thoughtfully "It's not finished?" I tell him that I still need to finish painting it. "Yes. Well when it is finished, perhaps I will make you an offer for it!" "You know my wife and I, we have sold our little house!" he says, "And we have moved into Reykjavik, a flat in the city, in the Funkisstile!" "The what?" "The Funkisstile! You do not have this word?" "I know the Jungendstijl, but I've never heard of the Funkisstile, is it an Icelandicthing?" "No. Everywhere they have the Funkisstile! It is the boxy! The boxy style!" he points to the shippingcontainers outside the window and in my drawing. "We love it!" I tell him that the Dutch, too, are also very fond of the Funkisstile. "Yes. Well I do not wish to disturb you!" "Thank you for these, Captain, I will take good care of them." "Yes."

Later I watch two tugs guide the big Maersk ship in. I count ten decks in their conning tower to our seven, but theirs was much wider, I wonder if they need more crew to operate a ship that large? After dinner, once it was docked at the quay, six behemoth cranes were engaged in loading and unloading it at once, we've only had two cranes working with us on one occasion. We're done in Goteborg by about 10pm, and I watch the Maersk ship lit up like Christmas as we roll back out into the Kattegak, the narrow sea between Sweden and Denmark.

22 July, Friday

This morning we are in the Danish port of Arhus. This port is entirely owned and operated by Maersk, and is very up to date. The terminal itself is a large rectangle of new land outboard of the older harbor. The Captain tells me that the eventual intent is to move all of the shipping to this new terminal and convert the area of the old port into "fancy housing". I suggest that it might be in the Funkisstile. "Yes." There are heavily loaded ships going back and forth to an area of shallow water next to the new terminal. They are dumping sand for the terminal's expansion, when this is complete It will be twice its current size. The newest areas of the terminal are even now just being graded and paved, and beyond that a new seawall is being put in place by construction ships as the sand is being offloaded. From the uppermost part of the Dettifoss, outside above the bridge, I have a view of the entire process: creating a new port where there was once open sea.

The Maersk facility is even more efficient than Goteborg. The harvesters used here are an improved design, with the cab placed in front instead of hanging off the side, this allows two harvesters to collect containers from adjacent rows without colliding. And they, like the cranes here, are painted a tasteful shade of powder blue that matches the Maersk Sealand containers that are neatly stacked everywhere. Think of the container facility as a giant desktop, the objective is to sort the items on the desktop into organized stacks, the Maersk port has a clearly visible outbox adjacent to the cranes, and an inbox along the narrow causeway access road where big trucks come through, the only link to the mainland. There is also a tidy parking rack for the harvesters off to the left. Building the port from scratch in open water has allowed Maersk to sort its desktop out just the way it wants, and the rapid loading process is the result.

There are lanes underneath the cranes between the tracks, and the smooth way in which the containers are placed exactly on the lines by the harvesters, and picked up swiftly by the cranes is either a testament to the skill of the operators or evidence that this process is already becoming locally automated. The big cranes will often be simultaneously performing all of their possible operations: sliding a few feet along the tracks, pulling in the grabber as it's being lowered and configured to the size and corners of the container. And it seems like the operators (or the software) are compensating to minimize swing as the containers are brought across and down, gracefully turning forward momentum into forward motion and lowering them before they have a chance to swing back. Very smooth. I wish I had a video camera.

This is how everything becomes a robot, small processes are automated and optimized bit by bit, not all at once. You don't make the entire crane automatic and then push a button and walk away, you throw a little algorithm in there that tests the heft of each container and swings it across just so. You don't let all the harvesters run around blind, you bury wires in the tarmac under the yellow lines to help the drivers drop the boxes accurately and swiftly. Kybernetes, just like on the ship, you keep humans riding along doing what humans are good at: dealing with unexpected conditions and unintended consequences: the stuff that falls through the grid of the software world map. Thinking of how graffiti artists paint freight cars, which then travel around the country, I can imagine some kind of future scenario where, once the ports are entirely automated, artists can break in and paint the containers as pixels, so that they'll make different patterns and shapes when they're stacked on ships and carried around the world.

We're back rumbling through the Kattegak after dinner at 18:30, on our way to Frederikshavn in Norway. I've just watched the Bilbao video that the Captain loaned me. "It's really funny because in the academic end of the architectural profession right now, everything has to be done for a reason." I tell him at dinner, "If you make a move or change something the first question is 'why?' " "Yes. Because there are so many things that can be done it's so important to stay open to different reasons!" "Exactly, that's why it's so great the things Gehry says about painting, he's open to all these other influences." "Yes." "And a lot of people say it's arbitrary, but I think it's highly complex and rational." "Yes. Of course!" I tell him that a lot of architects right now, especially in the states, are interested in making houses out of shipping containers. "Yes. Because you can buy them once they are no longer used. I have seen them used for the refugees!" "But architects are designing these houses for wealthier clients, it's a trend now even though very few have been built." "Yes. But this will be so ugly!" he says, and gives a short laugh. "It's the Funkisstile!" I say.

23 July, Saturday

What did I do all day? Read Dante. Watched my movies: Casablanca and Miller's Crossing. Too bad they're region 2 DVDs, these are good to have around, I ate all my cookies ...

Lunch was three kinds of fish, I could smell it from the outside of the ship, two decks up. The Captain was standing at the buffet table when I got to the galley: "That horrible smell is this!" he said, lifting up a lid "It is a skate!" It was greyish brown. "It is smoked, and then allowed to rot a little." he laughed. "Okay, I'll try some." I put a bite sized chunk on my plate. "And this is salted cod!" ordinary looking steamed fish, okay. "And here we have sauce for the fish, here is melted butter, and this! This is melted lamb's fat! Very good." I tried the butter. "What's this?" I asked, lifting up the last lid to find strange pieces of white plastic underneath. "Oh, this! I didn't know we had this! I would have had some! I'll have get another plate!" the Captain was getting nostalgic "I have eaten this since I was a boy! It is whitefish, steamed a little, and then dried to preserve it and then heated up again!"

The skate didn't taste as bad as it smelled, but I didn't want anymore after one bite. Later, the smell was everywhere, it had stuck to my clothes, even my skin, I changed my shirt and took a shower before I went to bed.

24 July, Sunday

I've gotten up late and am eating breakfast in the galley, talking with Jonas, when a chunk of land slides past the window, it's the southern tip of the Faroe Islands. I went up to the top of the ship to watch our approach to the harbor and it's a lot like I had pictured: tilted pieces of green and rocky island, bordered by cliffs and treeless, under a grey cold sky. The air is damp and chilly, and I'm thrilled to have to put on my coat for the first time. There are little clusters of tiny cartoon houses in sheltered spots on the shore, all painted different colors with different colored roofs too, some grass. The land when you see it through the mist is close in bands of rock and grass, all kind of crooked like the whole thing might slide back into the Atlantic someday. It's all dramatically lit by the overcast sky with breaks in the clouds casting shadows and spots on the hills, the wind is hard but the sea is calm for now.

The biggest patch of crayola houses is Torshavn, and for a minute I can't figure out where they're planning on docking the ship. The Captain executes a skillful stop just 50 meters from a sand and rock beach and we back into our parking space on the quay right behind a small Spanish cruise ship. No behemoths here, the Dettifoss uses its own cranes to unload, and there's only one scorpion dune buggy on the pier to pick the containers up and put them away. We'll only be here for three hours.

I walked into town with the German Tourists and since it's Sunday, everything is closed. The town is almost empty too, except for us and the other tourists from the cruise ship, everyone is at home or at church. Everything, even the boats, is brightly colored and small under the grey sky, and it must be so cozy to live inside a tiny house with a thick warm turf roof and a red door. I stop and draw one of the small streets with small cars and small houses and even a small, white, friendly, Faroese cat that wants me to scratch his ears.

It's a good place to keep in your head for mental vacations: wearing a sweater because it's 12 degrees centigrade in July and it's threatening to rain, taking walks from town to town on paths that are 500 years old, floating around in a sailboat that needs a new paint job when the sun comes out, living in a grass roofed house, in a tiny village, on a cloudy green island, in the North Atlantic.

Back on the Dettifoss I'm on the roof again when the Captain sticks his head up and asks me into the bridge. The ship has the best view of the harborand the town, we get binoculars and he points out buildings that he likes. "There is a rowing contest next week! Look, you can see the girl's team practicing there!" "They're all blond!" I say, "and strong!" "Yes." Below us half the crew is gathered in that corner of the ship, watching them and waving.

After we've left, passing the Russian trawlers in the harborand the Vestmanna bird cliffs, I spent some more time on the top of the ship watching the seagulls get a free ride to Iceland. The gulls here are all different and exotic, with matte black tops or mottled grey like stone, and there are four or five of them that skim along just a foot above the waves, surfing in a zone of turbulence that somehow moves faster than the ship itself alongside it. They almost never have to flap their wings, going all the way to the front of the ship before rising up into another layer of air that moves back and then churning around in the wake before doing it over again. How do they learn that they can do that? and how do they teach each other? It's tempting to see it as a kind of chaos theory metaphor (Surf the Gnarl!) until you remember that it takes a huge inefficient thing like a cargo ship burning literally tons of fossil fuels moving televisions from China to Iceland to generate enough free energy to carry four seagulls across the ocean. It's not sustainable, it's just hitchhiking. If the designers of the Dettifoss could, they'd have her slip through the air and the water so smoothly that she'd leave no surplus turbulence behind at all. Those vortices are extra energy draining away, the seagulls are just there to pick it up and put it to some use. And it it looks like it must be a lot of fun, they don't have to fly that close to the water probably, but when the sea is calm enough it sure is cool to try to see how near you can get to the wave without hitting it.

25 July, Monday

We have crossed two time zones in the past two days, setting the clocks back one hour on each occasion. This means we've gained two hours, always overnight, and the amount of daylight is growing again as we head north. If the meals weren't delivered at the same time every day my sense of when to sleep and when to wake would become totally unmoored. Clock time is drifting, solar time is drifting, only the meals keep me anchored to a predictable sleep/wake schedule. In order to hold the schedule together I have to maintain discipline in two areas: no naps longer than 1/2 hour, and I have to get myself up in the morning in time for breakfast. Yesterday I broke both rules, with a long nap in the afternoon and a late breakfast, and last night I was asleep by 10pm, and stayed in bed until 7am local time, with the extra hour from the time zone crossing I was in bed for 10 hours. We'll be rounding Iceland all morning today until we get to Reykjavik at 3pm, since this is the time I usually start to feel like napping, that should keep me awake, and since I've gotten up early by the clock, hopefully the bright sky won't keep me awake too long tonight.

I've spent most of the morning so far up in the bridge, talking about jazz and art with the Captain, and watching Iceland slide past through the binoculars. There are whole islands out there that are less than 40 years old. the ship went through a channel between a glacier on one side and a volcano on the other. The volcano is part of the Westman Islands, the newest island came up 1967: Surtsey. Biologists and geologists are asking people to stay clear of it so they can observe how the land develops and plants take hold.

We arrive in Reykjavik at about 4 pm, and within an hour the entire crew except Bragi, the First Officer, is packed up and gone. It's funny to see these guys all of the sudden clean up and change into decent clothes, they all get in cars with their wives carrying cases of tax-free beer. The shuttle bus that's supposed to take me across the terminal never shows up so the Captain and his wife offer me a ride into town, which is great because I have no local currency and no idea where to get some. They're worried about me: "Don't you know where you're staying?" No, my cell phone has turned on me again, refusing to connect to the Icelandic networks. I tell them that I have a few places in mind, and want to check them out. They drop me in the center of town and I realize how small this city is, about the size of Annapolis. The Captain gives me his mobile number and email address in case I need anything, and I'm off in Reykjavik to look for a place to stay.